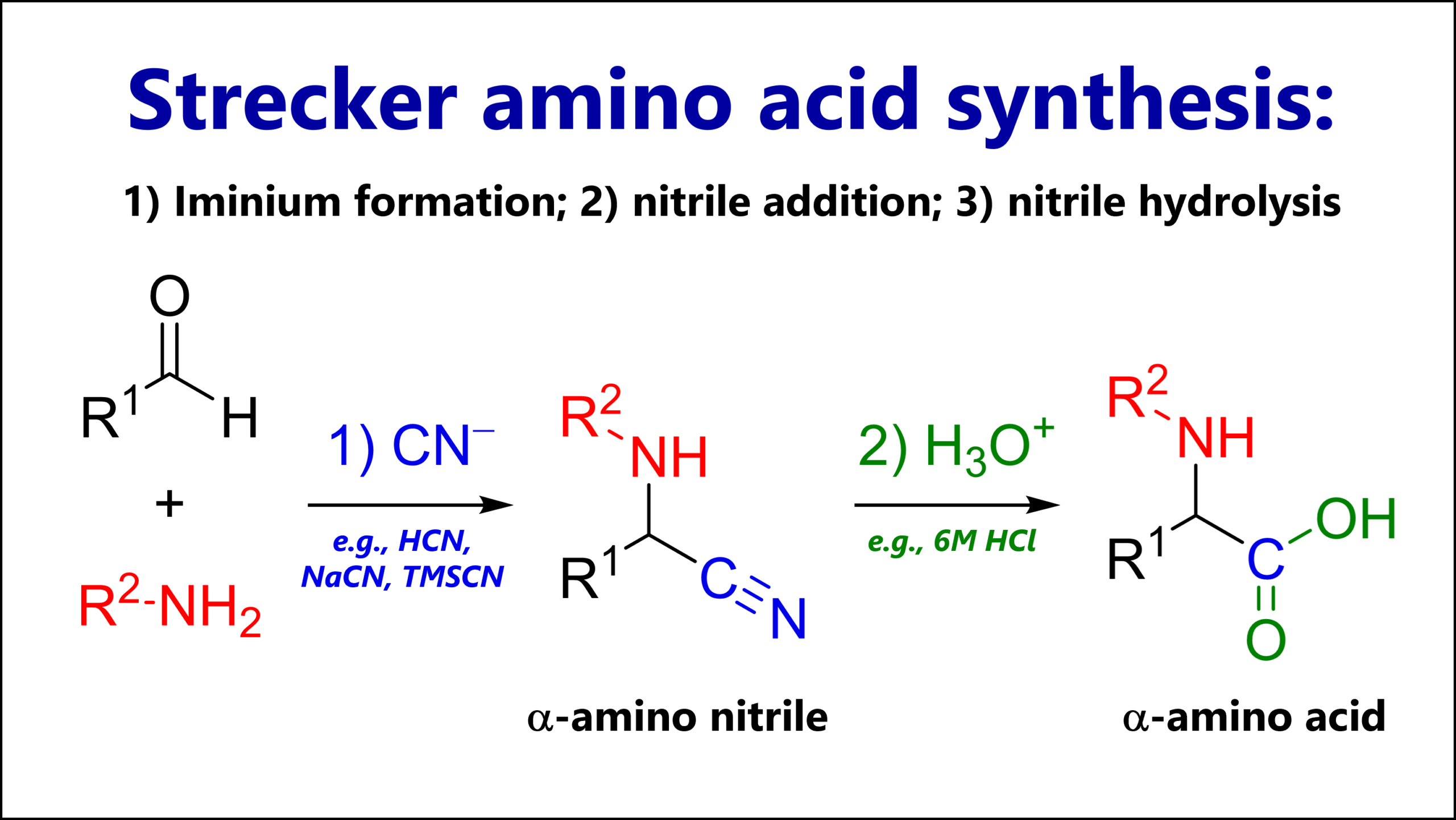

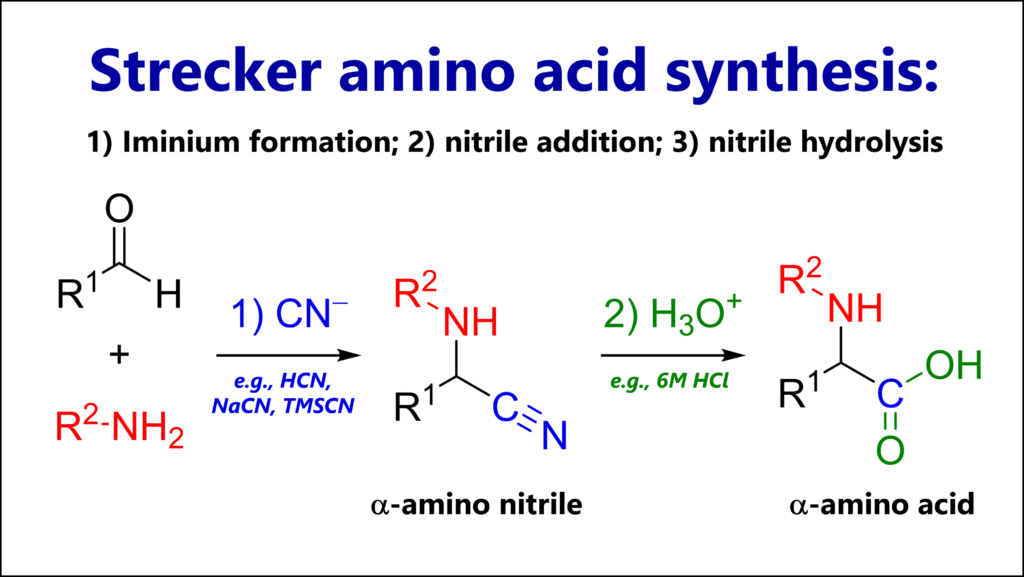

The Strecker amino acid synthesis is a reaction of a carbonyl (most commonly an aldehyde), an amine and cyanide. The key intermediate is an α-amino nitrile which can be hydrolyzed to an α-amino acid.

🫡 Here’s what you’ll learn in this article about the Strecker synthesis:

👀 Left: 3D structure of phenylalanine, an amino acid easily obtained with the Strecker synthesis!

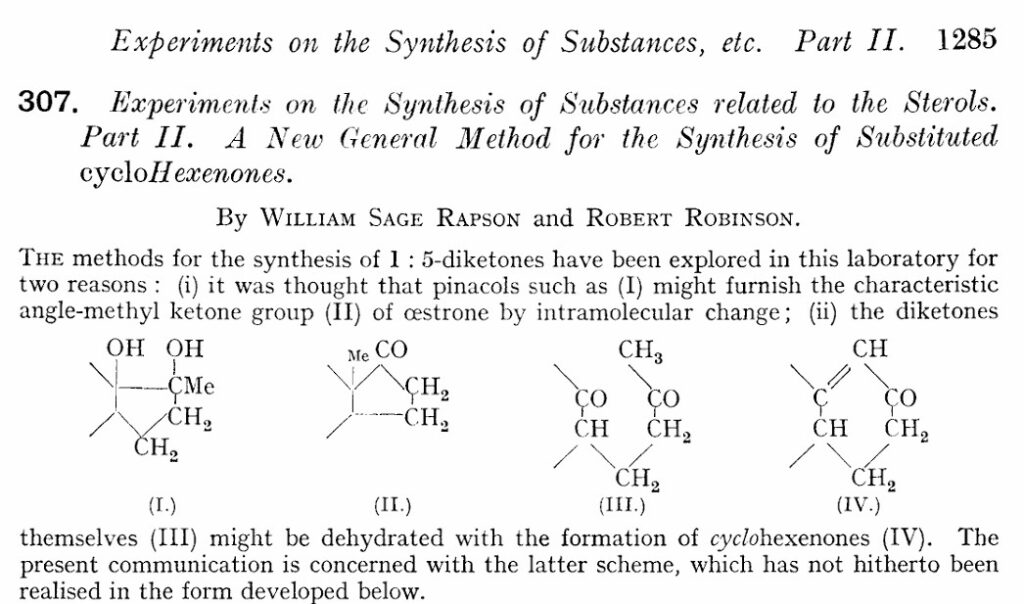

Why is the Strecker synthesis important?

Because it’s part of your exam. Jokes aside – the Strecker synthesis is one of the oldest but most powerful reactions in organic chemistry. It uses three components with simple functional groups – an aldehyde, an amine, and cyanide – to create α-amino nitriles and ultimately α-amino acids. This reaction might have been how amino acids were first formed on primordial Earth billions of years ago!

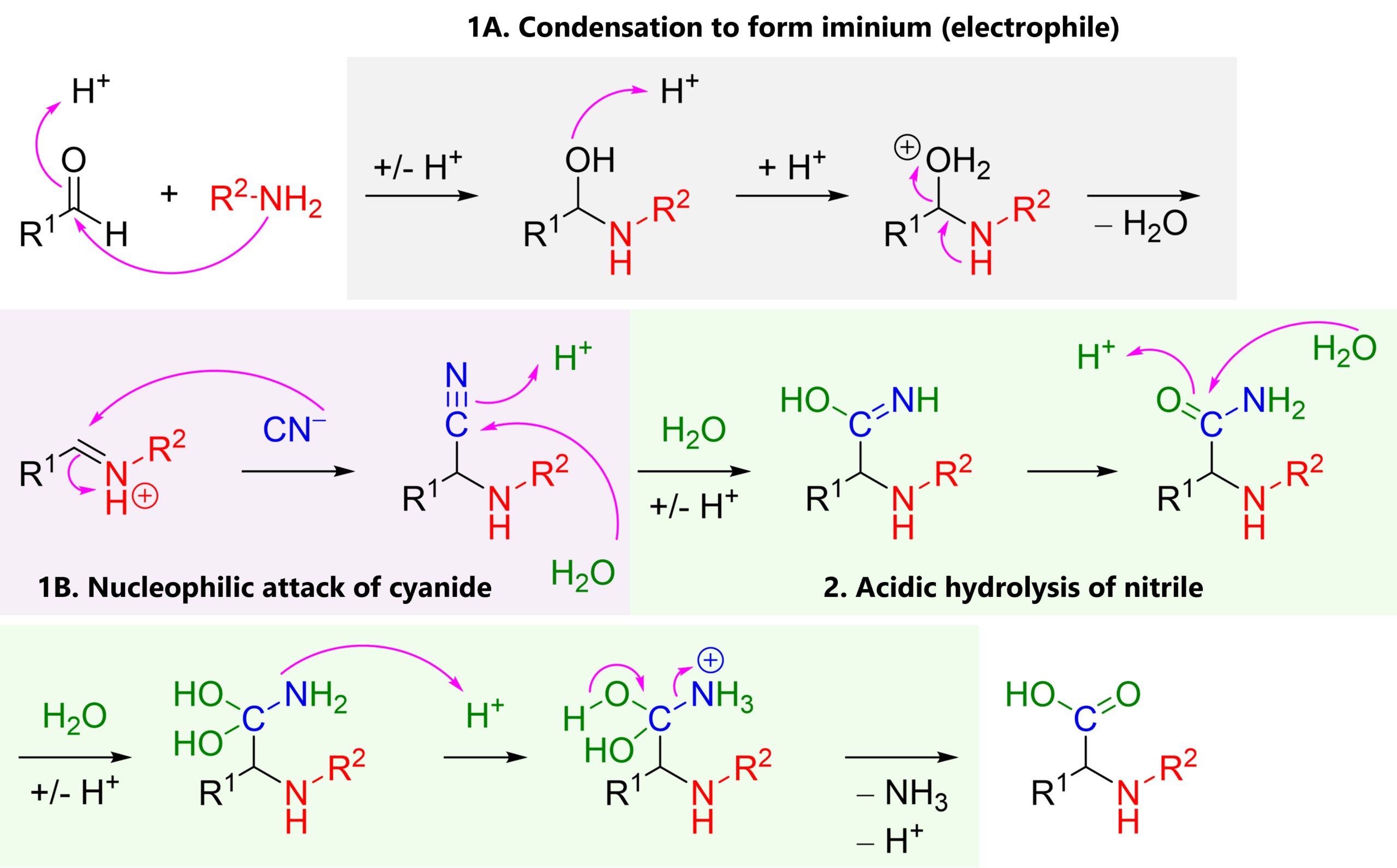

Strecker synthesis mechanism

The reaction mechanism of the Strecker synthesis follows three steps:

1A. Condensation of ammonia or an alkyl amine (nucleophile) with a carbonyl, most commonly an aldehyde (electrophile), giving an iminium cation

1B. Nucleophilic attack of cyanide (nucleophile) to the iminium (electrophile), giving an α-amino nitrile

2. Typically in a second experimental step: Acidic hydrolysis of the nitrile functional group, giving a carboxylic acid.

As we will see below, this is not the only thing we can do with the nitrile.

This is a polar mechanism (think: electrophile-nucleophile).

If the additions, protonations … are confusing, I suggest you look at your textbook’s chapter on carbonyl reactivity.

Also, remember that the CN– anion is called cyanide, but once it’s bound to carbon, the R-CN group is called a nitrile. In the Strecker synthesis, cyanide is a one carbon equivalent; a way to add one carbon into a molecule.

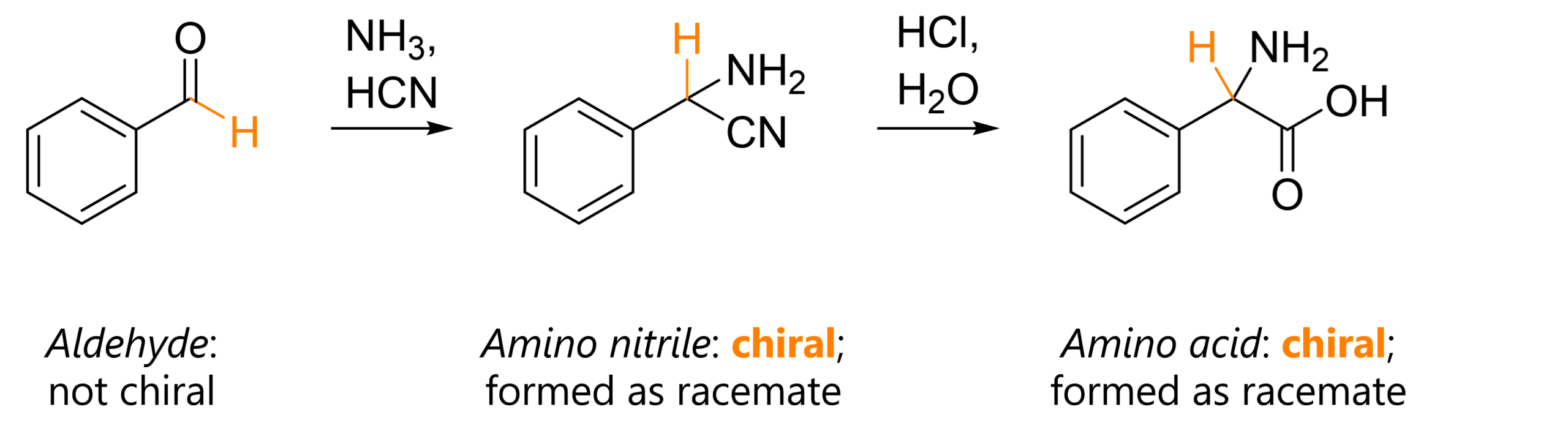

Note: The amino acid product has a chiral carbon. Unless our starting material has another chiral center already, or unless we perform an enantioselective reaction (details below), the product is formed as a racemate, a 1:1 mixture of enantiomers.

Conditions for Strecker amino acid synthesis

To achieve steps 1A and 1B, a range of reagents can be used. The classical conditions are NH3 + HCN, but HCN is extremely toxic and ammonia gas is not practical. Other cyanide sources like NH4Cl or NaCN + AcOH are safer and more practical, but just make sure you know the conditions mentioned in your lecture. Additional additives can include Lewis acids, to facilitate nucleophilic attack to the condensation product.

The classical conditions for step 2 are HCl + H2O with heat. This is rather harsh, because nitriles are very stable. To avoid side reactions with other functional groups in the molecule, chemists sometimes also use alternative conditions for this step.

I note some exemplary experimental procedures at the end.

Simple Strecker synthesis examples

Let’s get into some concrete examples: three easy, and two hard ones.

I. Synthesis of phenylalanine

The first is very simple – it’s the synthesis of phenylalanine, the molecule whose 3D model is shown at the start. Remember that the amino nitrile and amino acid are formed as a racemates (1:1 mixture of enantiomers) because after addition of the cyanide, the carbon has four different substituents.

II. Synthesis of unnatural amino acids

The second example is the first step of the synthesis of the unnatural amino acid methylvaline [4]. This example shows you that we can also use ketones, not just aldehydes, in Strecker syntheses. The difference is that that the central carbon is quaternary without a hydrogen substituent.

This reaction was done on a kilogram scale (see procedure below), so we can appreciate that NaCN was used instead of HCN. Later on in the synthesis, the racemate is separated into the two enantiomers, and the nitrile is hydrolyzed (not shown).

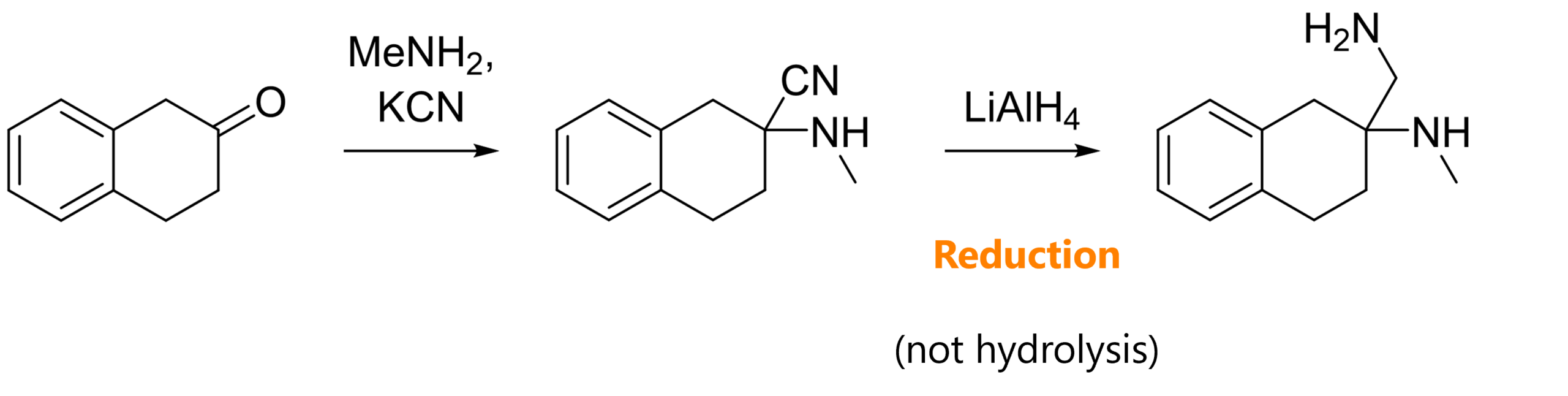

III. Reduction of amino nitriles

The next example shows that our first synthetic intermediate, the α-amino nitrile, can also be used for other reactions [5]. Instead of acidic hydrolysis, the nitrile can also be reduced to the amine with lithium aluminium hydride.

Alternatively, you might also see reductions with DIBAL-H to the aldehyde, or nucleophilic additions of Grignard reagents.

Tired of serious chemistry?

Take a break with “Periodic Tales – The Freshman Mole”, a satirical novel that’s the opposite of educational.

Dedicated to every chemistry and STEM student who asked: “Why did no one warn me?”

Advanced Strecker synthesis examples

The next two examples are more complex, intended for more advanced readers.

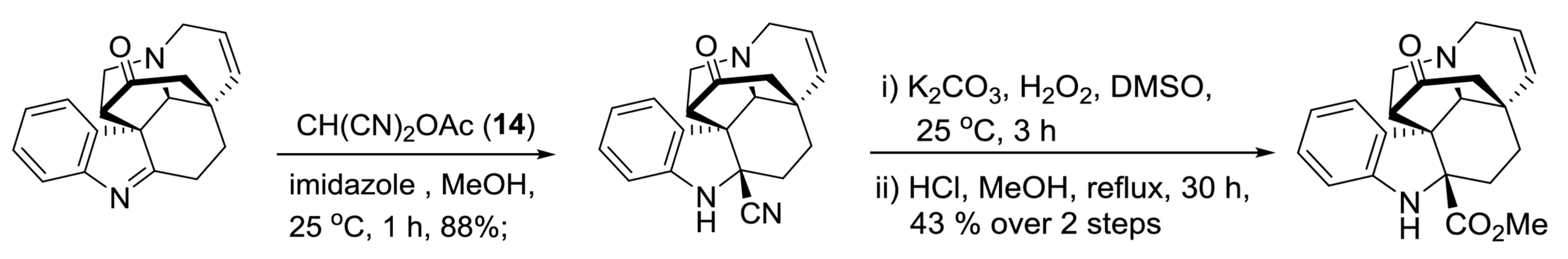

I. Lurbinectedin: Intramolecular Strecker synthesis

Can you figure out what’s happening in these three steps?

This example comes from a synthesis of lurbinectedin [6], an alkaloid natural product which is lung cancer treatment. The reaction sequence is:

1. Swern oxidation of the alcohol to the aldehyde;

2. Acidic deprotection of the Boc-amine, followed by intramolecular condensation to the aldehyde and addition of cyanide;

3. Deprotection of the benzyl protecting groups.

This example shows you that instead of adding ammonia or amines, a Strecker synthesis can also occur with nucleophilic amines already present in our starting material.

II. Flavisiamine F: No Condensation step

Our final example shows that our starting material electrophile might already come as an imine, and not as an aldehyde or ketone.

It also shows that chemistry can be quite complicated.

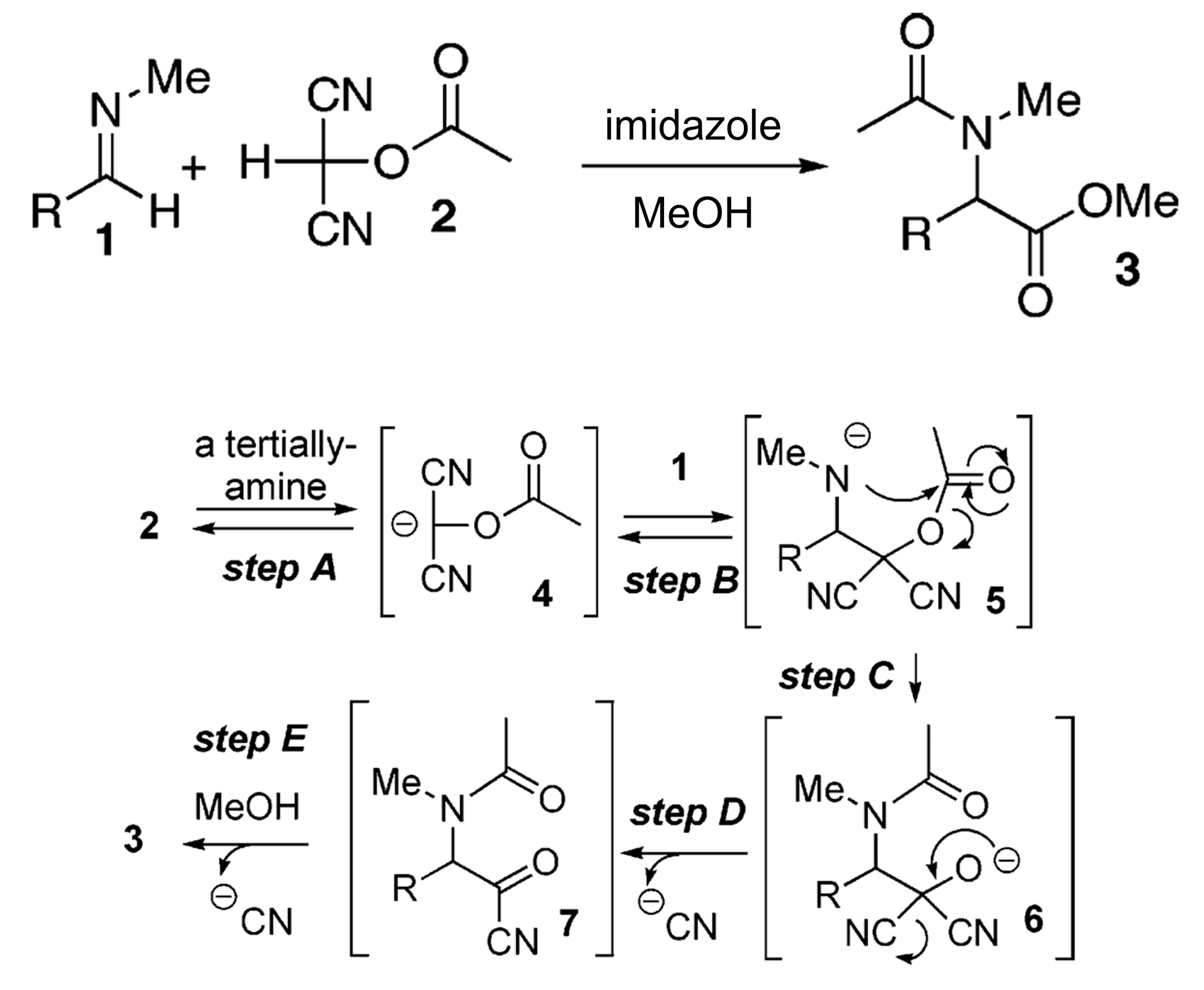

Why is CH(CN)2OAc used as the cyanide source?

Well, the chemists used this reagent because it was supposed to give the acyl cyanide, and finally the methyl ester product. In this case, they only obtained the nitrile (so they had to convert it with additional steps).

Here’s how the reagent should work in theory.

Pretty amazing (and confusing) that an unexpected side reaction occurs with 88% yield!

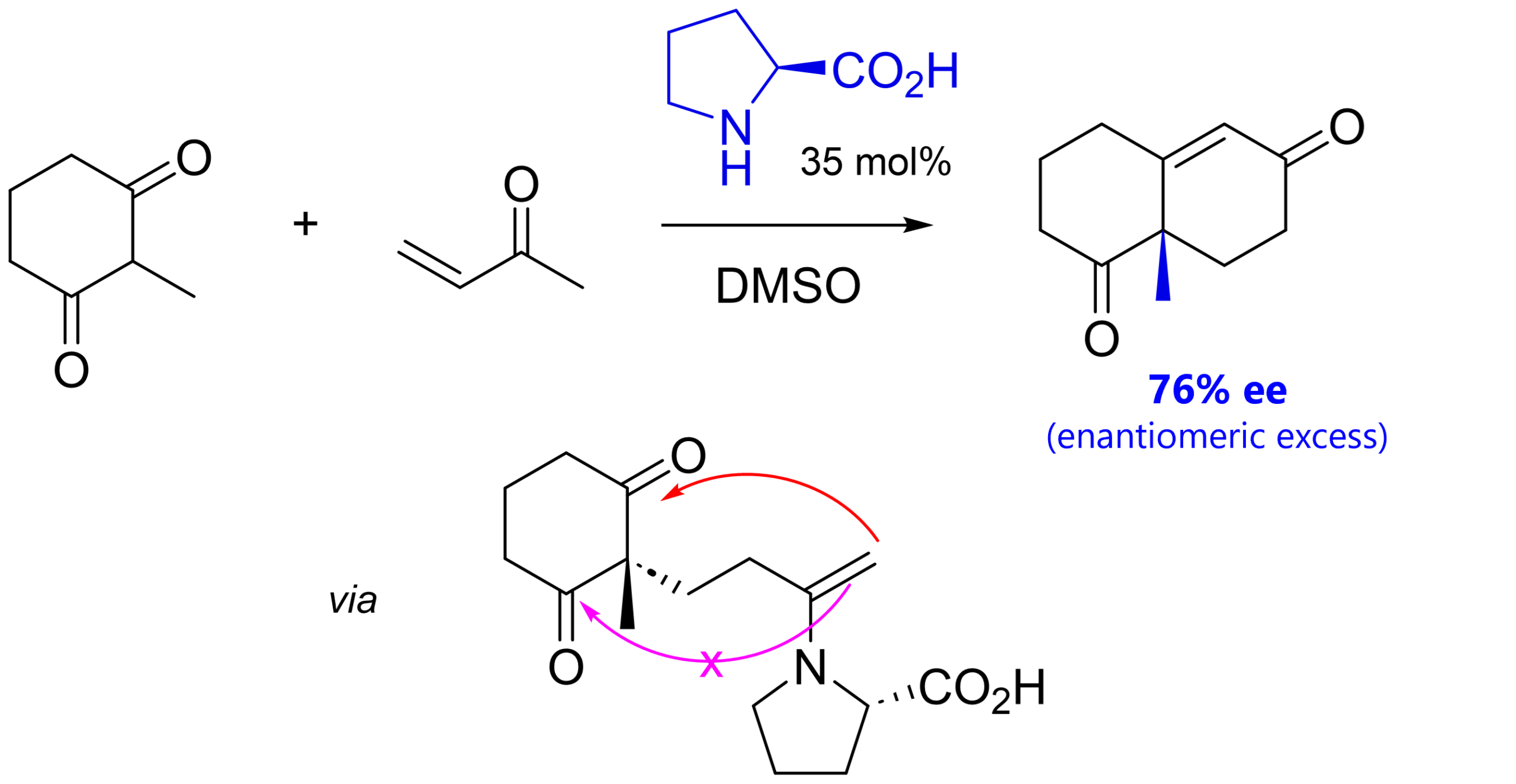

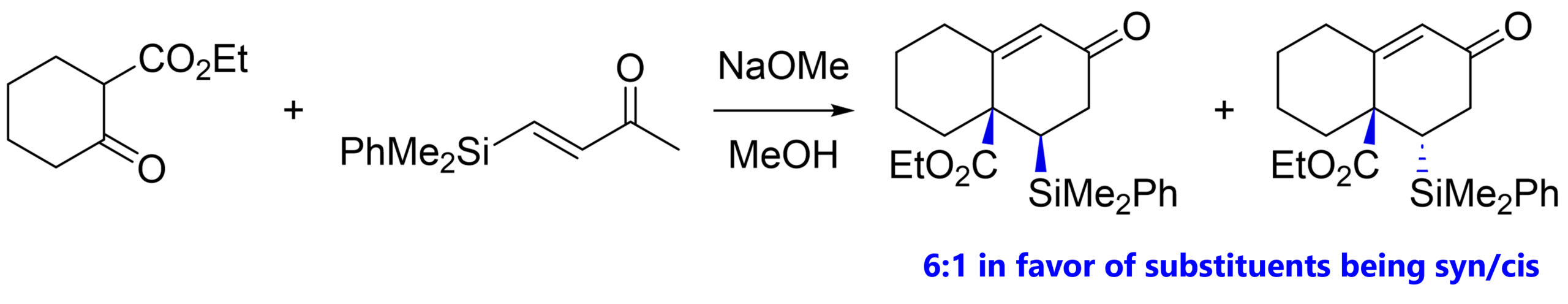

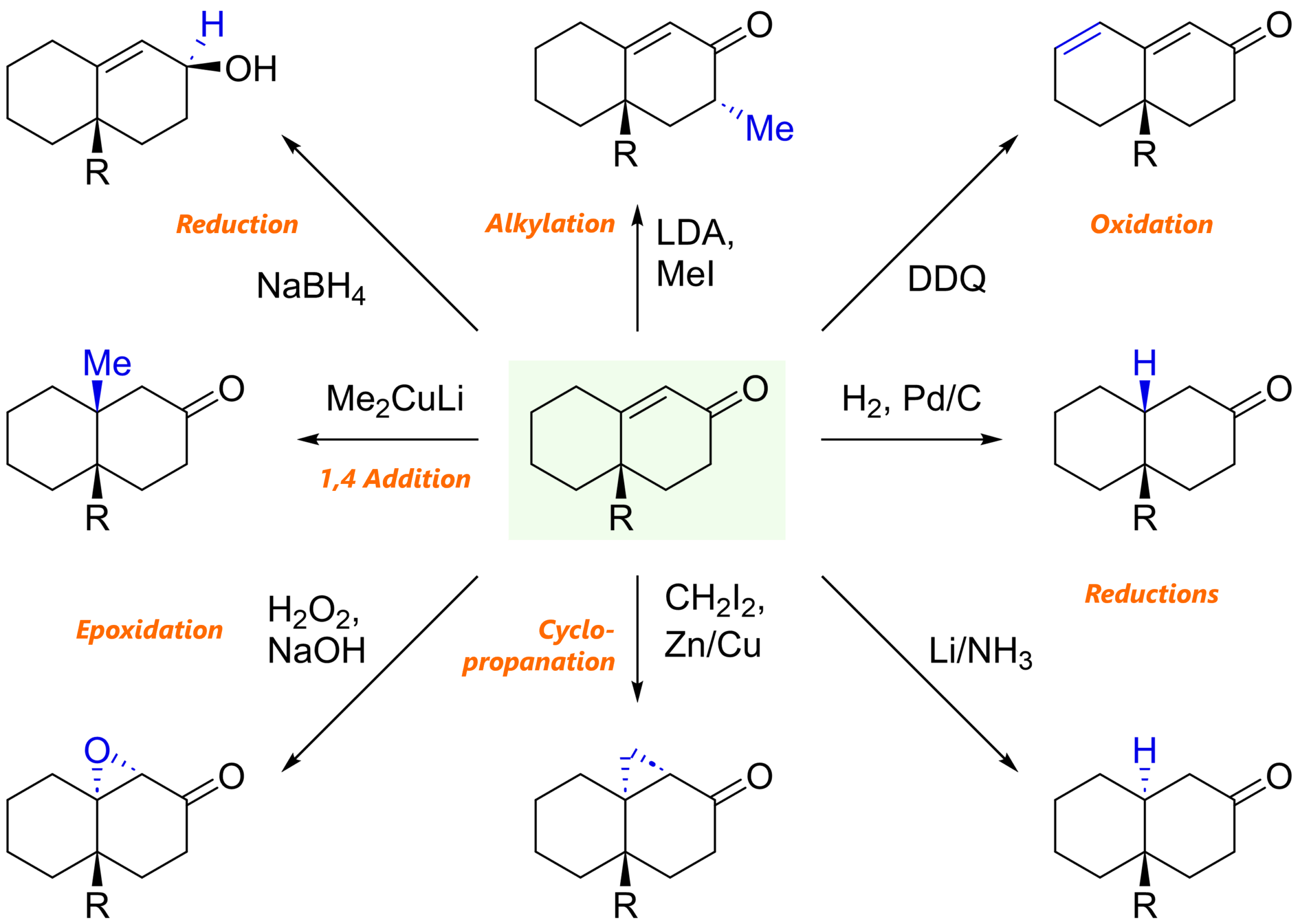

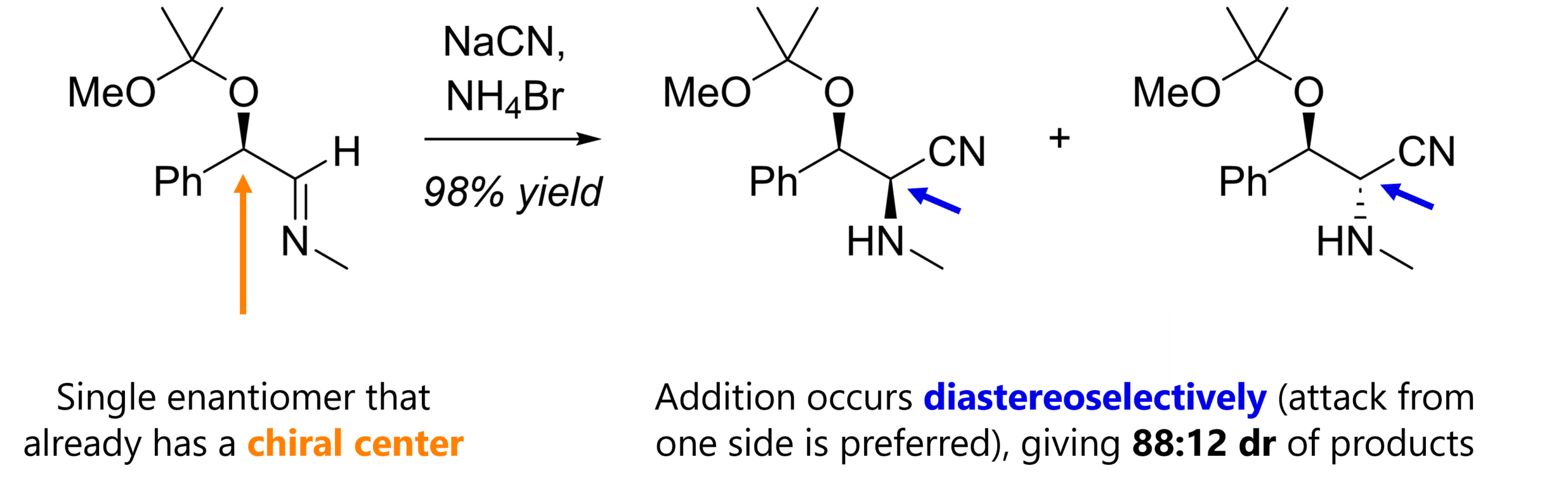

Diastereoselective Strecker Synthesis

Initially, we mentioned that “normal” Strecker reactions deliver racemic mixtures of amino acids. There are two cases where this does not happen.

The first is diastereoselectivity [9].

When our starting material already comes with a chiral center, the nucleophilic attack of cyanide will often prefer one approach over the other (because one side will be sterically blocked).

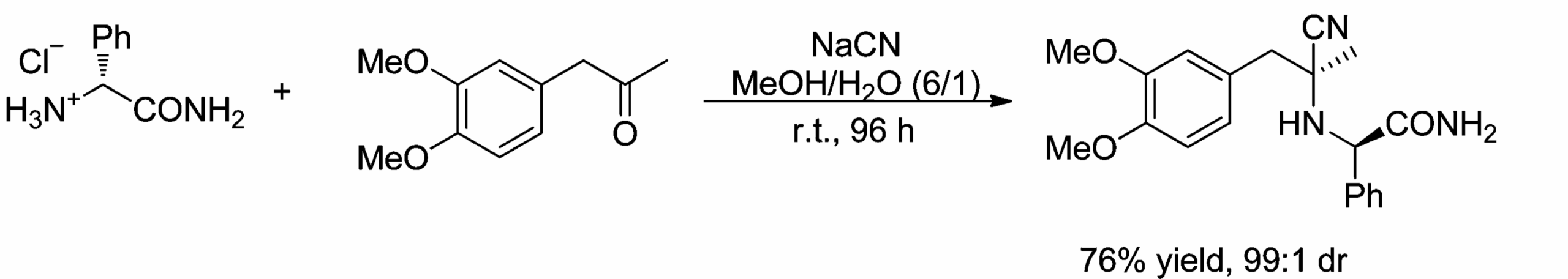

What I find really funny is that chiral amino acids themselves can be used as chiral auxiliaries! Below is a diastereoselective Strecker synthesis with (R)-phenylglycine amide. [9]

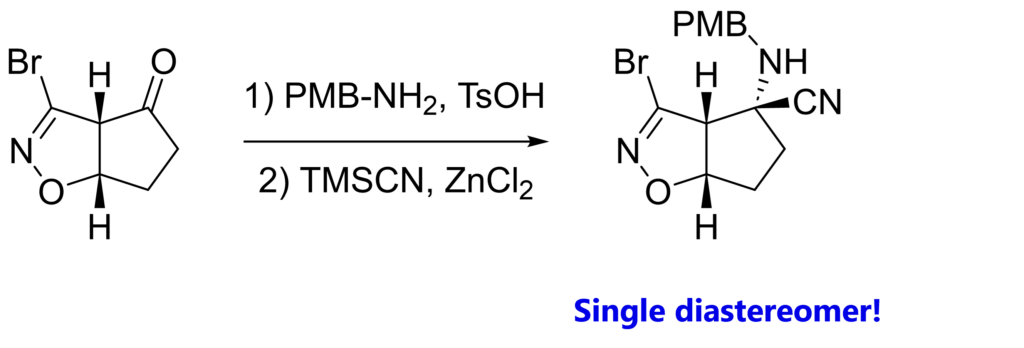

But beyond auxiliaries, we can observe diastereoselective reactions in any chiral starting material. Here’s an example of a perfectly diastereoselective Strecker reaction [9].

It’s all about how our starting material looks like in space. Let’s look at the 3D model.

With both hydrogens facing “up”, the very same top / convex face of the carbonyl is more accessible than the bottom / concave face. Our cyanide anion will try to avoid repulsion with the electron pairs of N, O and Br. (obviously, we also have condensation first, prior to nucleophilic attack)

Enantioselective Strecker Synthesis

The second way to obtain non-racemic products is the use of a chiral catalyst for enantioselective Strecker synthesis.

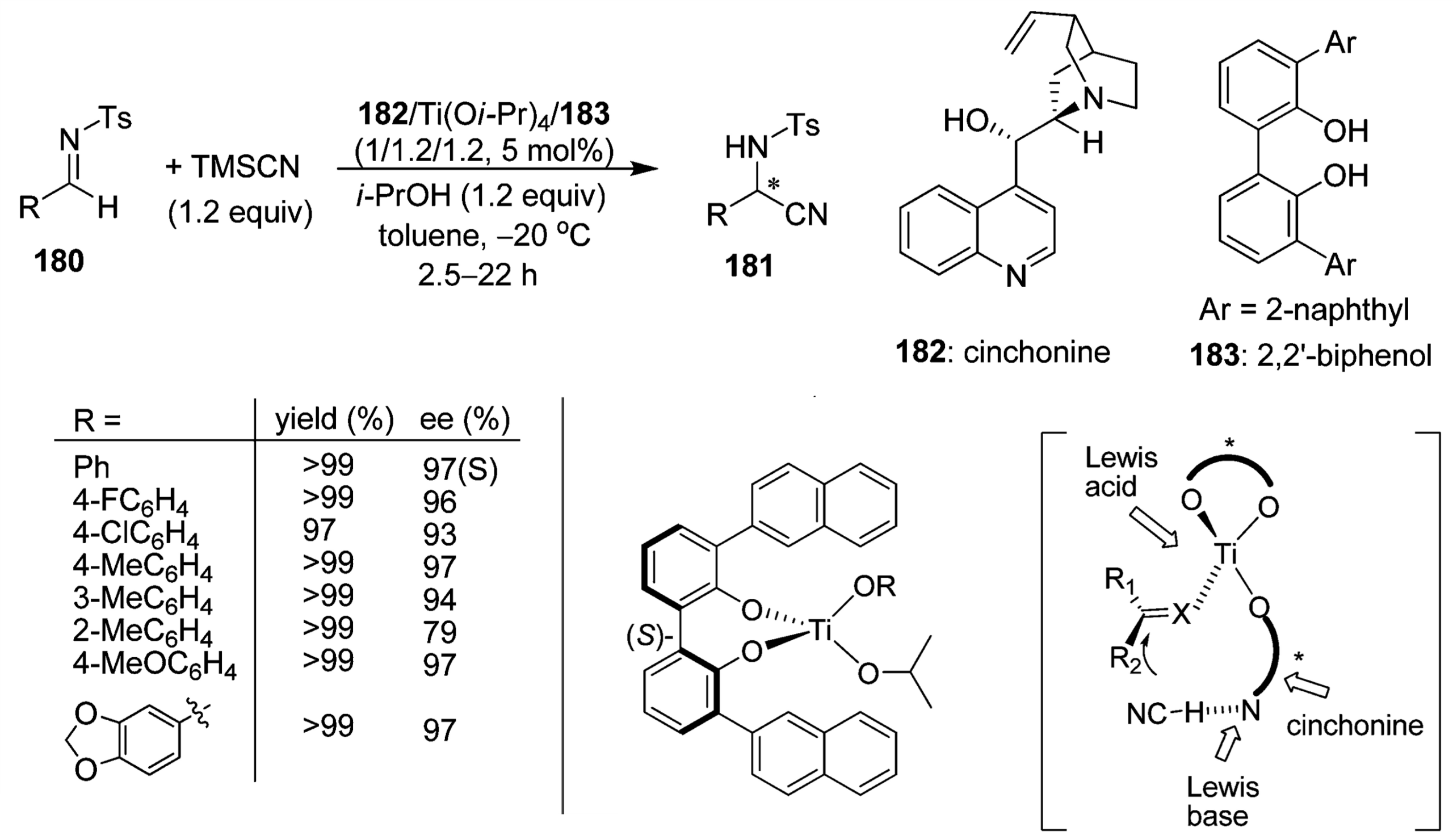

As just one example [9], below you see a catalyst system based on a titanium(IV) as a Lewis acid, a chiral biphenol ligand and a chiral cinchona alkaloid.

This is a “bifunctional” activation. Ti(IV) increases the electrophilicity of the carbon, while the cinchonine alkaloid base increases the nucleophilicity of cyanide. This is because the active cyanide reagent in the catalytic cycle is in fact HCN (and not TMSCN). Pretty surprising! The ligands create a chiral environment around the electrophile, thus leading to very high ee (enantiomeric excess).

Many other catalysts have been discovered.

History of the Strecker synthesis

I thought we wrap up with general context on this reaction. It goes way back. It’s named after the German chemist Adolph Strecker. This guy was a student of Justus von Liebig, one of the principal founders of organic chemistry.

Strecker first reported the reaction way back in 1850, making alanine from acetaldehyde, ammonia and HCN [1][2]. In his paper, he wrote:“The larger crystals of alanine are mother-of-pearl-shiny, hard and crunch between the teeth.” 😂

Notably, the first documentation of this reaction was even earlier, in 1838, by chemists Laurent and Gerhardt [3] (you see, you don’t always need to be first to have a reaction named after you).

This makes it the first multicomponent reaction in organic chemistry. In comparison, the Petasis reaction (another multicomponent reaction to prepare amino acids) is much younger, having been reported only in 1993.

Strecker was quite the productive chap. He also discovered the Strecker degradation (oxidative decarboxylation of α-amino acids) and the Strecker reaction (synthesis of alkyl sulfonates) – not to be confused with the Strecker synthesis of amino acids.

This is it for this article. Feel free to check out other articles on my page or my educational videos!

Classical Strecker synthesis: Synthesis of Alanine [10]

“131 g (3 mol) of freshly distilled acetaldehyde is added to 100 cc. of ether in a 2-l. bottle and cooled to 5 °C in an ice bath. 180 g (3.4 mol) of ammonium chloride dissolved in 550 cc. of water is then added, followed by an ice-cold solution of 150 g (3.1 mol) of NaCN in 400 cc. of water. The sodium cyanide must be added slowly and with frequent cooling to prevent loss of acetaldehyde by volatilization. After the sodium cyanide solution is added, the bottle is stoppered securely, placed in a mechanical shaker, and shaken for four hours at room temperature. At the end of this time the solution is transferred to a 3-l. distilling flask and 600 cc. of concentrated hydrochloric acid is added. […]”

Strecker synthesis with HCN experimental procedure [11]

“A solution of imine (0.2 mmol) and chiral catalyst (4.0 μmol) in methanol (1 mL) under a positive pressure of nitrogen was cooled to -25 °C. Liquid HCN (2.0 mmol) was added dropwise by chilled syringe to the solution, which was stirred at -25 °C for 12 hours and warmed to room temperature. Methanol and excess HCN were removed by evaporation, water (3 mL) was added and extracted with ether (3 mL). After drying (MgSO4), the organic layer was evaporated to afford the crude amino nitriles.

The amino nitrile (1.0 mmol) was suspended in 6.0 N HCl (1.0 mL) and heated to 60 °C. After 6 h, the reaction was cooled and washed with diethyl ether (2 x 1 mL). The aqueous layer was then neutralized with saturated ammonium hydroxide and the amino acid collected as a crystalline solid by filtration.”

Large-scale Strecker synthesis experimental procedure [4]

“In a 75 L round-bottom flask equipped with a mechanical stirrer, condenser, and thermocouple was added 2.79 kg (23.2 mol) of MgSO4, 1.24 kg (23.2 mol) of NH4Cl, and 2.16 kg (44.1 mol) of NaCN. The solids were slurried in 26.5 L (185.6 mol) of 7 M NH3 in MeOH and cooled to −5 to −10 °C. The internal temperature of the slurry was −5 °C and rose to 8 °C after stirring for 10 min as some of the solids dissolved. To the resulting suspension was added in one portion (4.00 kg, 46.4 mol) of 3-methyl-2-butanone 4. The internal temperature slowly rose from 8 to 35 °C over the course of 1 h, at which point it slowly decreased to 30 °C and was held at this temperature for 3 h (total reaction time 4 h). The reaction was judged complete by GC analysis at this point. […]. The final 1H NMR assay was 4.3 kg of 5 (87%).”

Strecker amino acid synthesis References

- [1] Ueber die künstliche Bildung der Milchsäure und einen neuen, dem Glycocoll homologen Körper | A. Strecker | Justus Liebigs Annalen der Chemie 1850, 75, 27

- [2] Ueber einen neuen aus Aldehyd – Ammoniak und Blausäure entstehenden Körper | A. Strecker | Justus Liebigs Annalen der Chemie 1854, 91, 349

- [3] Ueber einige Stickstoffverbindungen des Benzoyls | A. Laurent, and C. F. Gerhardt | Liebigs Ann. Chem., 1838, 28, 265

- [4] A Concise Synthesis of (S)-N-Ethoxycarbonyl-α-methylvaline | J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 7469

- [5] Design, synthesis, and structure-activity Relationships of a new series of alpha-adrenergic agonists | J. Med. Chem. 1995, 38, 4056

- [6] Synthetic Approaches to the New Drugs Approved During 2020 | J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 9607

- [7] Enantioselective Total Synthesis of (+)-Flavisiamine F via Late-Stage Visible-Light-Induced Photochemical Cyclization | Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 5443

- [8] A Highly Efficient Carbon−Carbon Bond Formation Reaction via Nucleophilic Addition to N-Alkylaldimines without Acids or Metallic Species | J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 14546

- [9] Asymmetric Strecker Reactions | Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 6947

- [10] dl-ALANINE | Org. Synth. 1929, 9, 4

- [11] Asymmetric Catalysis of the Strecker Amino Acid Synthesis by a Cyclic Dipeptide | J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 4910